Pabellón de la República Bolivariana de Venezuala en la 18° Exhibición Internacional de Arquitectura La Biennale di Venezia

CIUDAD UNIVERSITARIA DE CARACAS WORLD HERITAGE SITE IN RECOVERY UNIVERSITY CITY OF CARACAS

The Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas, headquarter of the Central University of Venezuela, was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2000 for “representing a masterpiece of human creative genius” and “being an outstanding example of a significant architectural ensemble for the history of mankind”, both for its buildings, urban planning, as well as for its integration with nature and modern art. It represents an exceptional universal value, which transcends the borders of our country because of its interest for present and future generations of all mankind.

Venezuela joins the “Laboratory of the Future”, proposal of this Architecture Biennial 2023, becoming a new center of knowledge production, where new narratives, tools, spaces, and architectural projects offer the possibility of building a better society.

We accept the challenge proposed, wishing to share the learning and experience acquired in the professional recovery of these heritage monuments of modern architecture.

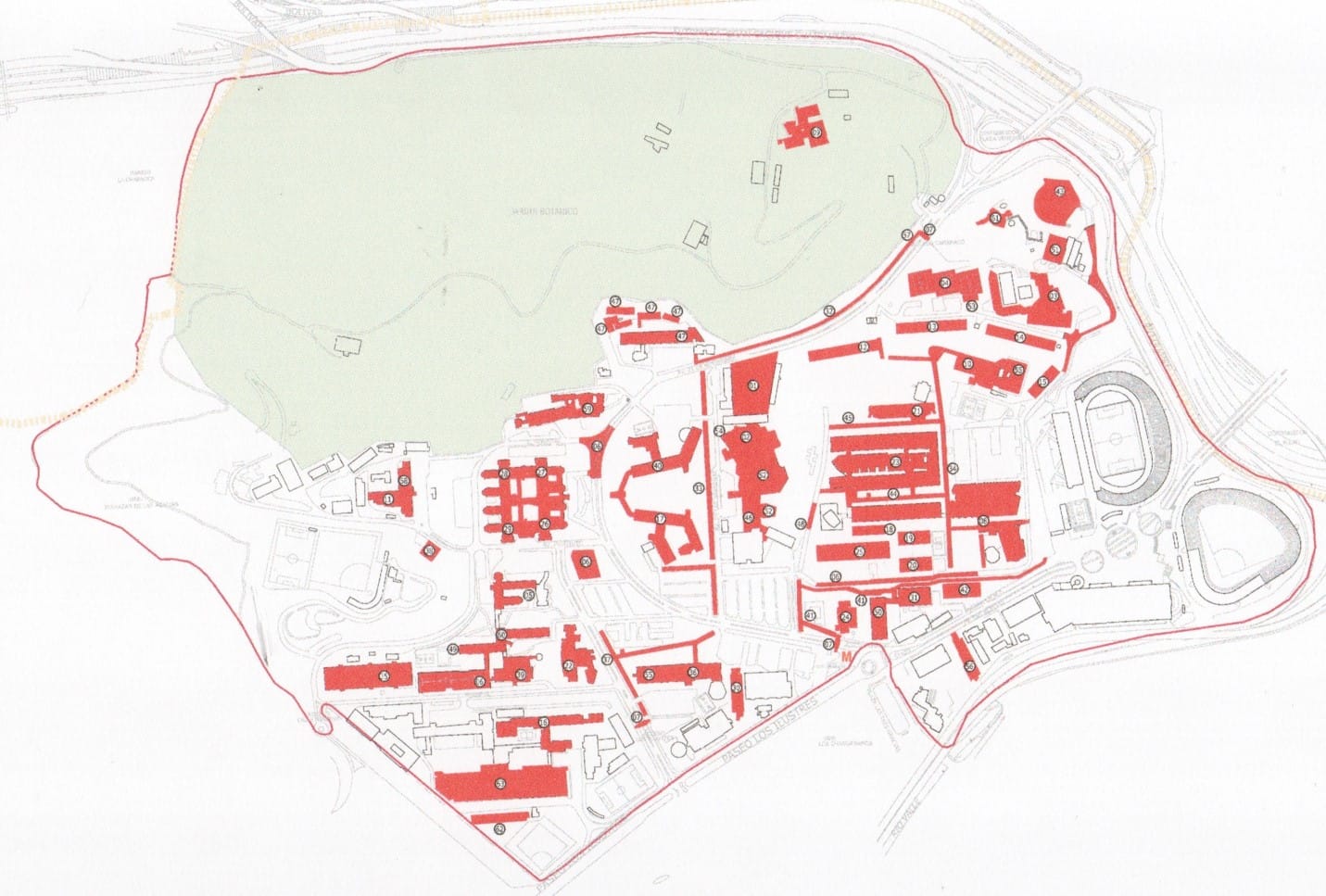

The main campus in Caracas of the Central University of Venezuela (UCV) currently has 100 buildings housing nine faculties, various administrative and research offices, cultural, sports, and hospital services, 108 artworks, and 92 hectares of green areas, whose recovery and maintenance motivated the President of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro Moros, to create the Presidential Commission for the Recovery of the UCV, integrated by teams of professionals, advisors, and inspectors from different areas such as restoration, landscaping, engineering, restoration and maintenance of artistic works.

The exhibition we are presenting at this Venice Biennale – Architecture 2023 is a collection of 20 months of work, “helping to imagine a common future, more equitable and optimistic”.

The campus of the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas C.U.C. headquarters of the Central University of Venezuela has:

An area of 164 hectares of which 95 are green spaces.

A Botanical Garden.

The University Clinical Hospital.

100 buildings linked to each other with 2 km of roofed corridors.

108 artworks integrated into its architecture.

It is an integrated center of higher education where hundreds of students, professors, employees, and citizens gather daily in its academic, research and outreach, cultural, sports, and medical care facilities.

The heritage restoration project currently underway is being carried out by 150 specialized professionals, some as advisors, and others as inspectors. This group is made up of architects and engineers from the Central University of Venezuela, working together with renowned construction companies.

The restoration project includes controlled demolitions, reconstructions in accordance with the original C.U.C. project, restoration of spaces and their original use, renovation of furniture in classrooms, amphitheaters, and laboratories, analysis of colors and their application where appropriate, as well as restoration of the original landscaping.

Of the 100 existing buildings in the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas, restoration and maintenance work are currently underway in 63 of them, including the University Hospital, in 3 public spaces: the Plaza del Rectorado, the Plaza Cubierta and the Plaza Jorge Rodríguez (popularly known as “Tierra de nadie” – “No Man’s Land”), in the sports facilities and intensively in the landscaping of the complex.

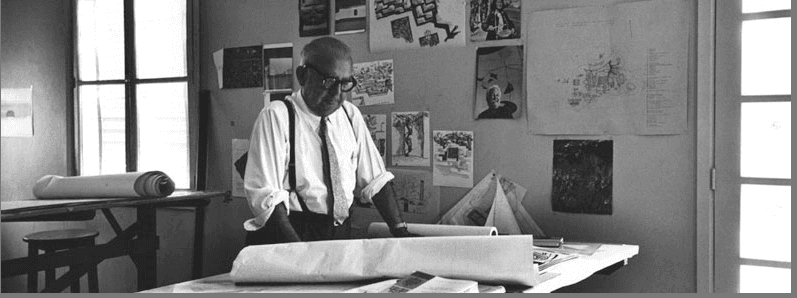

CIUDAD UNIVERSITARIA DE CARACAS 1943/1972

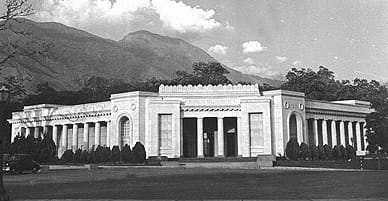

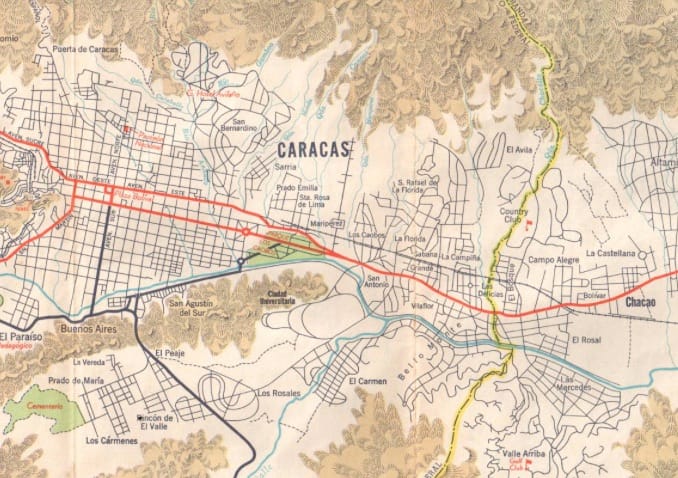

On January 5, 1944, Villanueva designed his first proposal for the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas. Influenced by his academic background, he follows neoclassical references using a compositional axis composed of the University Hospital to the west and the Olympic Stadium to the east. In a new proposal of the same year 1944, he began to relocate the different buildings of the complex, still using the initial compositional axis.

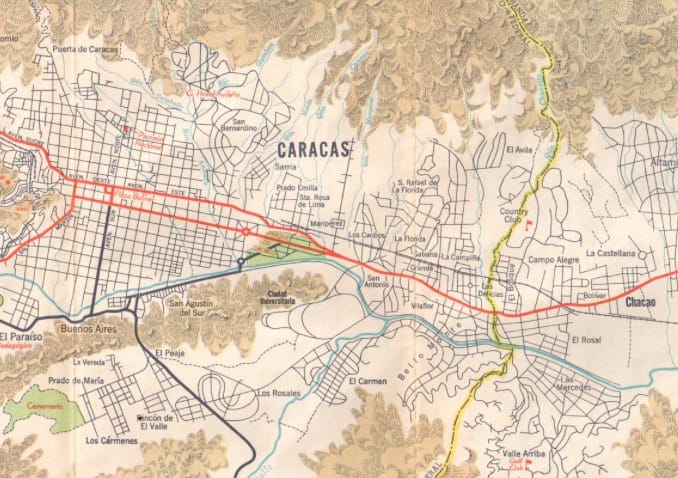

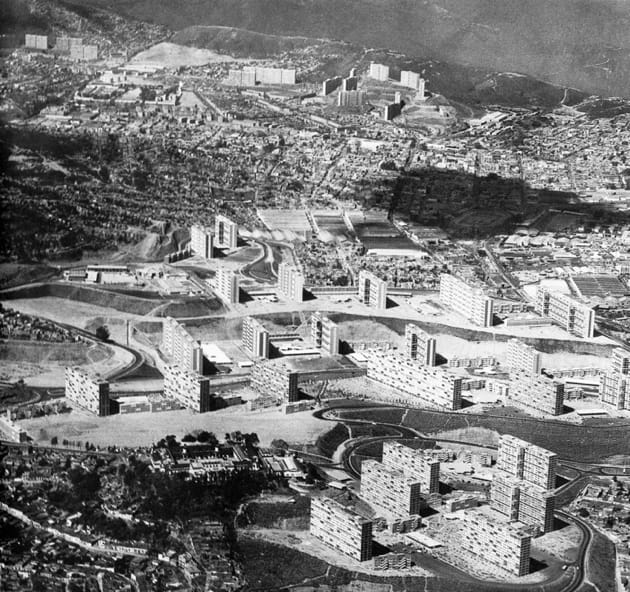

On January 5, 1944, Villanueva designed his first proposal for the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas. Influenced by his academic background, he follows neoclassical references using a compositional axis composed of the University Hospital to the west and the Olympic Stadium to the east. In a new proposal of the same year 1944, he began to relocate the different buildings of the complex, still using the initial compositional axis.  He progressively adjusted his conception of the complex by using references from modernity (Le Corbusier and the vibrant Brazilian architecture) up until 1962 when, after reconsidering “the climate, the breezes, the rain and the landscape, the geology, the vegetation, the light, the scale, and the environment”, he gave us this magnificent complex where only the location of the Clinical Hospital and the sports stadiums were kept from the initial proposal, creating this architectural masterpiece.As a result, due to the uniqueness of its urban planning, architecture, and art, UNESCO recognized and included it as a World Heritage Site in the year 2000.

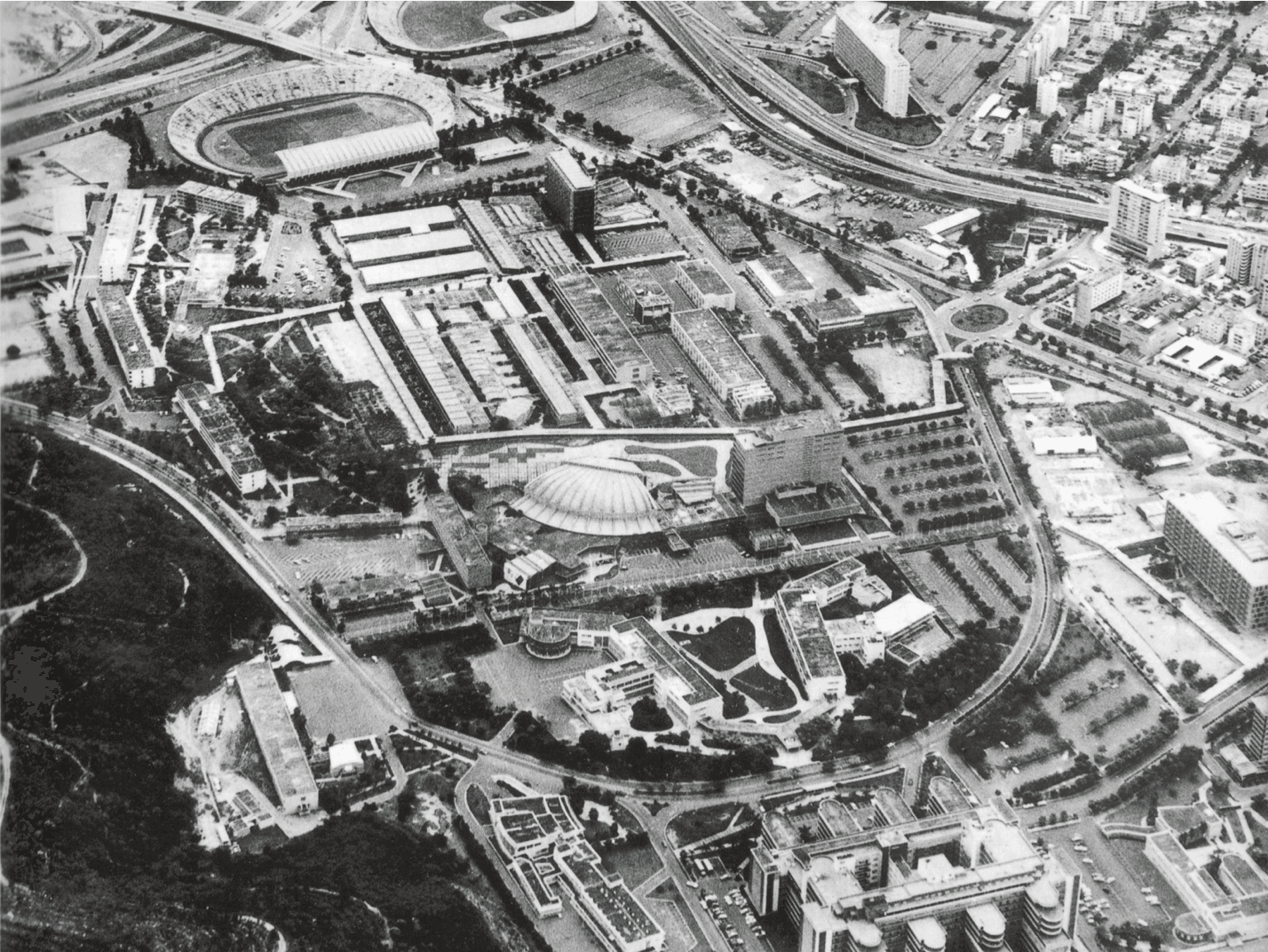

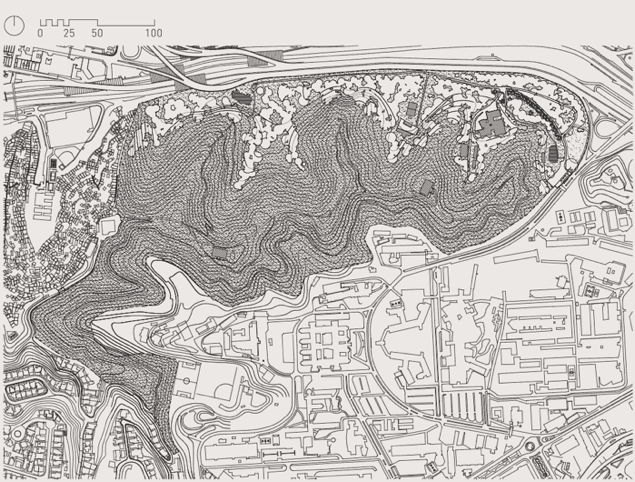

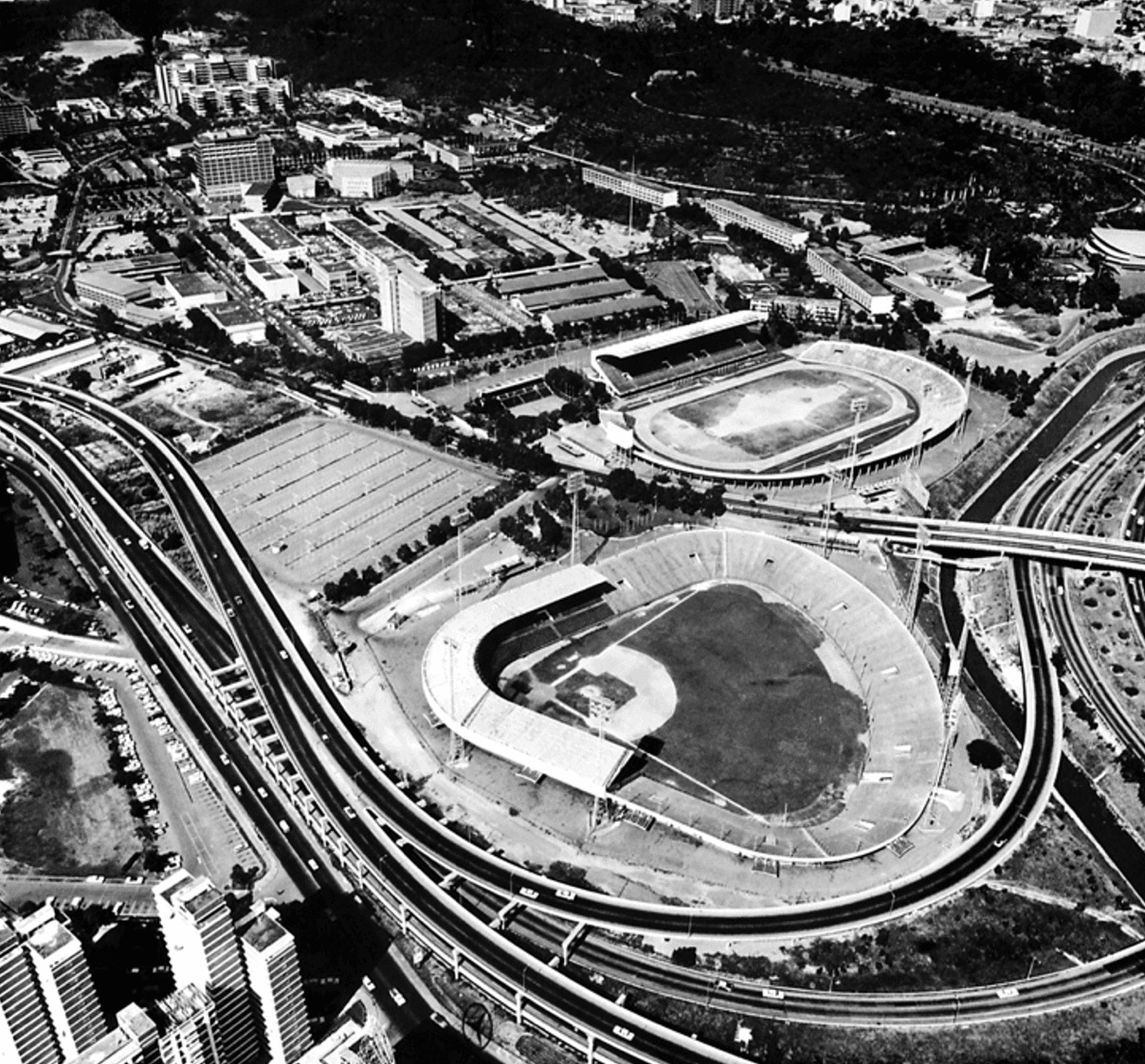

He progressively adjusted his conception of the complex by using references from modernity (Le Corbusier and the vibrant Brazilian architecture) up until 1962 when, after reconsidering “the climate, the breezes, the rain and the landscape, the geology, the vegetation, the light, the scale, and the environment”, he gave us this magnificent complex where only the location of the Clinical Hospital and the sports stadiums were kept from the initial proposal, creating this architectural masterpiece.As a result, due to the uniqueness of its urban planning, architecture, and art, UNESCO recognized and included it as a World Heritage Site in the year 2000. An aerial photograph of the campus of the Universidad Central de Venezuela in 1962 and a plan of the current campus.

An aerial photograph of the campus of the Universidad Central de Venezuela in 1962 and a plan of the current campus. The restoration and maintenance projects currently underway in the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas include:The three public spaces: the Plaza del Rectorado, the Plaza Cubierta, and the Plaza Jorge Rodríguez (popularly known as “Tierra de nadie” (No Man’s Land).The 5 accesses to the university2 km of covered walkways22.5 km of internal roads (including 40 sidewalk access ramps).Works in 46 buildings (31 of them are teaching and research buildings):541 classrooms, 154 laboratories, 5 amphitheaters, 12 laboratories, 248 faculty offices and lounges, and 275 bathrooms.In addition, improvements were made to the pool and gymnasium complex, tennis courts, and artwork at the Technical School.A total of 28.203 lighting units were installed in interior spaces and 1.724 outdoor floodlights and lights were installed in exterior areas. An area of 152.741 m2 of flooring was recovered.Regarding the landscaping of the university complex, 67.000 m2 of grass and ornamental plants were planted, 6.870 trees were trimmed and given phytosanitary treatment, 1.600 meters of a new irrigation system were installed, and 79 trees and chaguaramos (Caribbean royal palm) were transplanted.

The restoration and maintenance projects currently underway in the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas include:The three public spaces: the Plaza del Rectorado, the Plaza Cubierta, and the Plaza Jorge Rodríguez (popularly known as “Tierra de nadie” (No Man’s Land).The 5 accesses to the university2 km of covered walkways22.5 km of internal roads (including 40 sidewalk access ramps).Works in 46 buildings (31 of them are teaching and research buildings):541 classrooms, 154 laboratories, 5 amphitheaters, 12 laboratories, 248 faculty offices and lounges, and 275 bathrooms.In addition, improvements were made to the pool and gymnasium complex, tennis courts, and artwork at the Technical School.A total of 28.203 lighting units were installed in interior spaces and 1.724 outdoor floodlights and lights were installed in exterior areas. An area of 152.741 m2 of flooring was recovered.Regarding the landscaping of the university complex, 67.000 m2 of grass and ornamental plants were planted, 6.870 trees were trimmed and given phytosanitary treatment, 1.600 meters of a new irrigation system were installed, and 79 trees and chaguaramos (Caribbean royal palm) were transplanted. Clinical University Hospital

The complete restoration of the hospital is currently underway and is arduous due to the fact that work must be done while the health center is still in operation. The complex planning and programming of the work have already made it possible to restore, in accordance with Villanueva’s original project, several of the pavilions, consulting rooms, medical services, internal circulations, façades and terraces.

1/2. Two rooms of the Children’s Pavilion restored with original colors and lamps.

3. General view of the Children’s Hospitalization Pavilion, nurses’ station in the background.

4. The internal hallway in the Children’s Pavilion

5/6. An office and an internal staircase of the hospital

7/8 Interview room for psychiatric patients

9/10. Interventions in hallways and exterior spaces of the building

11. View of a floor Terrace of the University Clinical Hospital.

12. The main access to the hospital corresponds to the original axis of the campus layout designed by Maestro Villanueva, which connects it through an underpass to all the buildings of the Faculty of Medicine.

UNIVERSITY CLINICAL HOSPITAL

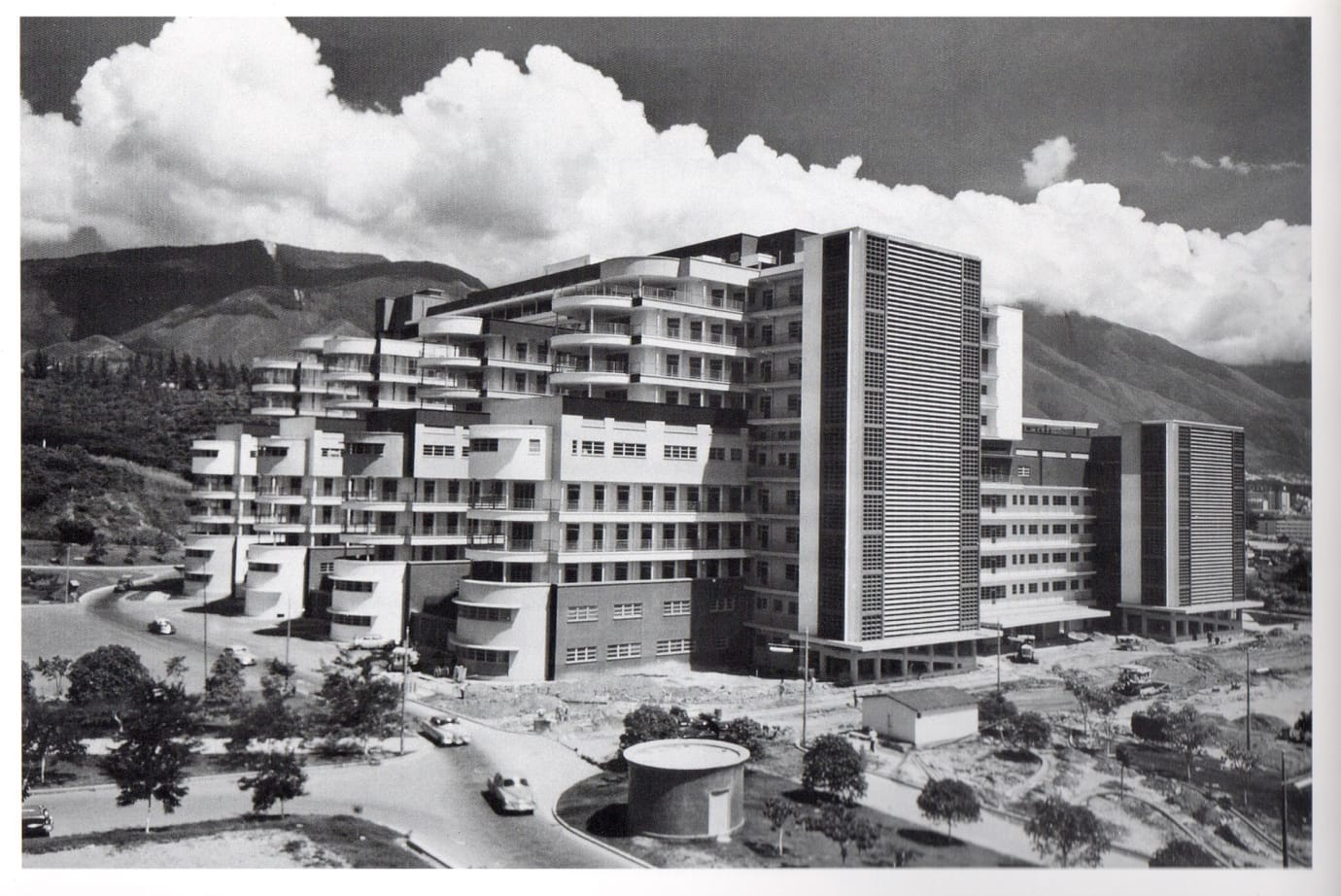

One of the first buildings designed for CUC was the University Clinical Hospital, which between 1944 and 1945 was progressively defined by Master Carlos Raúl Villanueva in collaboration with the firm Pardo, Proctor, Freeman & Mueser Consultants, R. Ponton and Thomas E. Martín, Armando Vega and Hernán De Las Casas.

The hospital opened in 1955, with 1,250 inpatient beds (later expanded to 1,658 beds). The building has 14 floors and two mezzanines, 10 elevators and two freight elevators, 4 ramps, 6 operating rooms with overhead lighting and observation domes for physicians and students, a pharmacy on each floor, a centralized kitchen (serving 3,500 meals daily) and a laundry.

The group of buildings of the School of Medicine were designed by C.R. Villanueva between 1944 and 1945, being built simultaneously and completed in 1952.

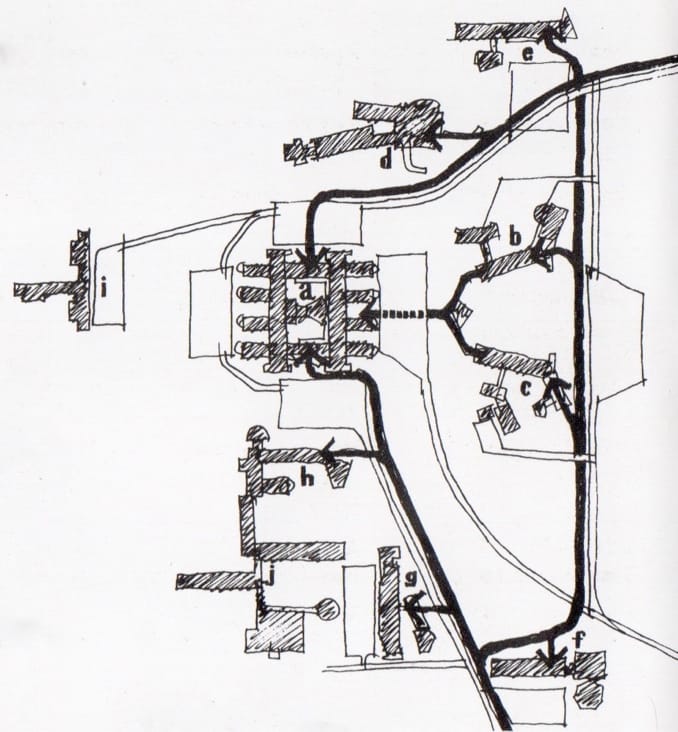

The group of buildings of the School of Medicine is composed of the following:

a. Clinical Hospital

b. Anatomical Institute

c. Institute of Experimental Medicine

d. Institute of Anatomic Pathology

e. Institute of Tropical Medicine

h. School of Nurses / School of Basic Medicine Luis Razetti

i. National Institute of Hygiene

Later, the following buildings were designed and constructed: f. School of Pharmacy (1955-1957) and g. School of Dentistry (1956-1960).

Construction chronology of the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas

Medical School buildings complex

Institute of Experimental Medicine

It is one of the seven research institutes under the Faculty of Medicine. It is mainly dedicated to basic scientific research, improvement of teaching, and promotion of health services.

Anatomical Institute

This is the second institute of the School of Medicine, which through research transfer and divulgate innovations in basic medical sciences, both at the clinical and experimental levels.

Completed in 1949, it opened three years later, allowing the transfer of medical students from the old and inadequate building built in 1911, located next to the Vargas Hospital.

Institute of Anatamopathology and Institute of Immunology.

The first of these two institutes included in 1949 in the initial program of the C.U.C., trains physicians in the field of morphological diagnostics: biopsies, autopsies, and cytology. The activities of the Institute of Immunology are focused on research, teaching, and clinical care services in the areas of Clinical Immunology and Basic Immunology.

Anatomical Institute

The Anatomical Institute’s main building during general repairs to restore its original state.

In this building, it was completed the restoration of the facade, eaves, and windows, the recovery of the glass block walls, metallic ironwork, painting, and waterproofing.

The auditorium and teaching laboratories restored

Institute of Experimental Medicine

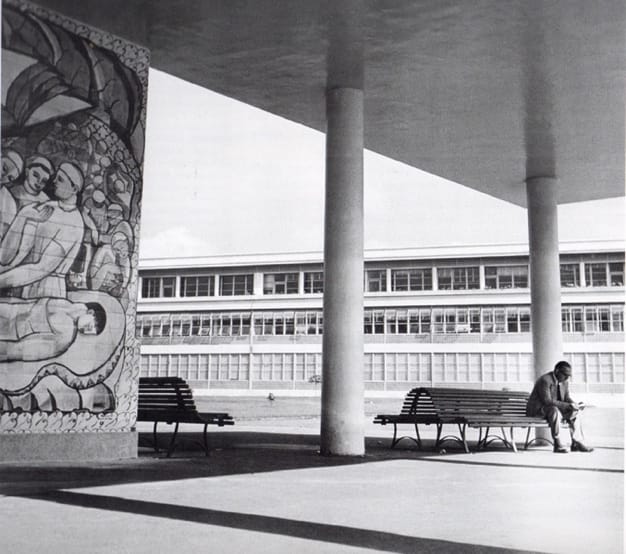

The main building of this Institute, named after Dr. José Gregorio Hernández, is another of the restored buildings. At the end of the terrace, there is the artwork “Educación”, made in Cumarebo stone by the artist Francisco Narváez.

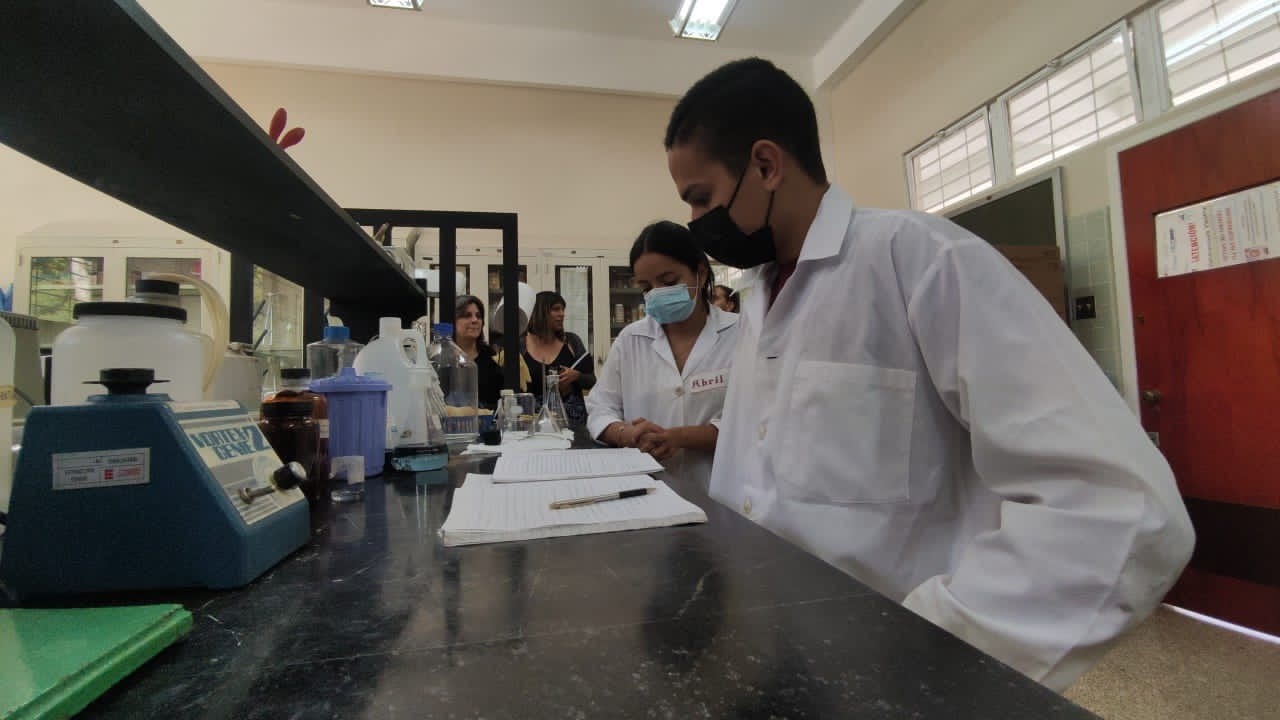

The original space of the Institute’s teaching laboratory has been restored recovering its structures by removing the ceiling, installing new lighting fixtures, painting the ceiling, walls, and windows, as well as equipping it with new furniture and optical equipment.

Works chronology of the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas

School of Medicine buildings complex

These buildings of the School of Medicine were also designed by C.R. Villanueva between 1944 and 1945, being built simultaneously and completed in 1952.

National Institute of Hygiene.

This institute, created in 1938 and named after “Rafael Rangel”, is an independent entity of national reference for diagnosis, development of biotechnologies, research on endemic diseases, sanitary control of products for human use and consumption, production of experimental animals, as well as teacher training.

National School of Nurses

Designed between 1943 and 1953 and completed in 1955, the building consists of a 2-story classroom building, a 4-story residential building, and a 2-story service building, all three connected by vaulted corridors.

Institute of Tropical Medicine

This institute is the national reference center for research, extension and undergraduate and graduate teaching of tropical medicine, microbiology and parasitology of the School of Medicine.

Medical Institutes.

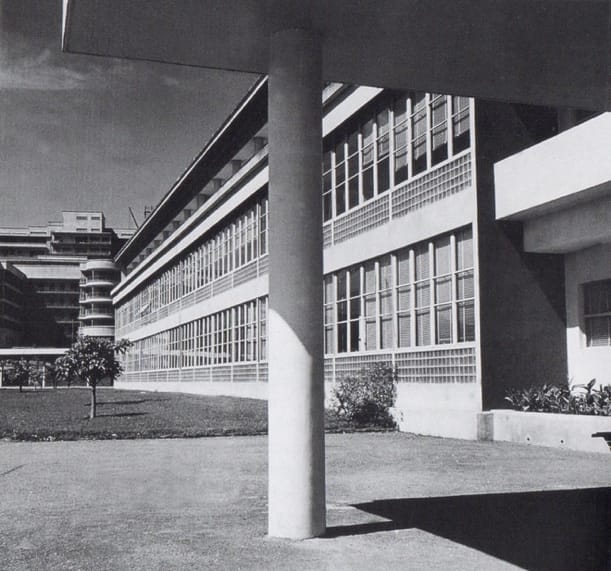

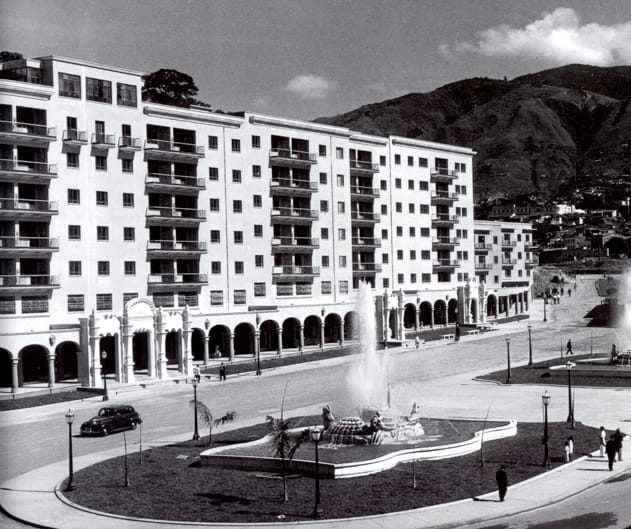

Considered by architectural critics as transitional buildings between the Escuela Gran Colombia (1939), the urbanization of El Silencio (1941), the Industrial Technical School – ETI (1946-1947), and his masterpiece of the central complex of the Rectorate, Plaza Cubierta, Aula Magna and Central Library (1952-1953), these buildings underline the ambivalent character of the architecture and the urban approach of this first stage, which is basically characterized by:

- The role, in urban terms, played by the buildings of the Institutes of Experimental Medicine, Anatomy and Clinical Hospital, as fundamental structuring elements of the urban relations of the first campus designs of 1943 and 1944, based on the use of symmetry as a resource of organization and centralized hierarchization of the plan, an overall approach whose academic roots are attributed to the Beaux Arts training of CARLOS RAUL VILLANUEVA.

- The character of “spare units” attributed to the buildings of the Institutes of Anatomical Pathology and Tropical Medicine, since their peripheral location is not dependent on the main system of axial relations of the aforementioned complex.

- The modern approach to the architecture of the six buildings is functionally and formally resolved, in contrast to the academic character of the urban approach,

Considering this perspective, a possible re-reading of this first stage should start from the assumption that Carlos Raúl Villanueva (CARLOS RAUL VILLANUEVA) does not have a dissociated conception of architectural space and urban space. On the contrary, his conception fully coincides with what, years later, Bruno Zevi (1948-1976. p 28) will define as the double responsibility of every work of architecture: simultaneous creation of “the internal spaces, completely defined by each architectural work, and the external or urbanistic spaces, which are delimited by each of them and their contiguous ones”. This idea is confirmed by the first images of the campus ideation process, present in the overall plans of 1943 and 1944, where the buildings of the Clinical Hospital, the Institute of Experimental Medicine, and the Institute of Anatomy, which structure the urban spatial conception of the campus in neoclassical language, appear prefigured in plan with the same characteristics that would later be developed in the executive project, between 1945 and 1947, by the independent technical engineering firm of Pardo, Proctor, Feeman, Feeman & Mueser, Consulting Engineers, with the architectural advice and supervision of CARLOS RAUL VILLANUEVA. This is clear evidence that by 1943 the early prefiguration responds to the existence of a complete development of the architectural blueprint, simultaneous with the development of the urban plan for the campus.

This reinterpretation requires a radical change in the critical reasoning. Instead of considering this first stage as a process that begins with an academic urban conception, by using a modern language of architecture, it should be seen as part of a fully modern architectural research process, which, for circumstantial reasons, uses urban terms in academic language.

From this perspective, the six buildings of the first stage, including the special case of Hygiene, do not constitute a parenthesis within CARLOS RAUL VILLANUEVA’s architectural search but are part of its patient research, as a common thread and without a solution of continuity. This development has among its most significant previous links the fundamental experience in terms of education and modern architectural language of the Escuela Gran Colombia of 1939; the architectural and urban experience of El Silencio of 1941, from which he rescues the fully modern architectural language with which he makes explicit the environmental relationship of the internal courtyards and the houses. From 1946-1947 Villanueva experiences the synthesis of the Industrial Technical School in which, taking inspiration from the Escuela Gran Colombia, he articulates the functions of housing, services, administrative areas, laboratories, and natural environment, using open spaces and the covered corridor as an articulating element, and explores the technological possibilities of concrete and steel for the solution of the larger spaces, such as the dining room and the laboratories.

In this process of architectural reflection, the academic conception associated with the ideation process of the urban complex approach of the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas, can be described as what Giulio Carlo Argán (1973. p17) calls an architecture of composition which will evolve into the fully modern conception of architecture of formal determination. The architectural synthesis that is already present in the ETI is nourished by the experience of the process of exploration of the structural possibilities and language of concrete, through the design of the covered walkways (1948), and of the University Stadiums (1949-1952). In addition, Villanueva’s parallel exploration of the dining area and social spaces of the School of Nurses building (1953) will result in the architectural and urban synthesis of the buildings of the central administrative and cultural area in 1952 and 1953.

In relation to this process of urban spatial composition and with the criticisms formulated about a relative lack of unity between the central complex, composed of the buildings of the Clinical Hospital and the institutes of Experimental Medicine and Anatomy, and the supposedly “free” institutes of Pathological Anatomy and Tropical Medicine, the architectural critics coincide in underlining the generically neoclassical roots of the first stage of the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas, associated with the use of symmetry as a resource of organization and hierarchy of urban planning represented in the buildings of the Clinical Hospital and the institutes of Experimental Medicine and Anatomy. On the other hand, not much is said about the properly classical sense with which are conceived the four buildings of the medical institutes, including those of Pathological Anatomy and Tropical Medicine, as an integral part of the relations between unity and urban totality of this first stage of the 1942-43 plan. The ideation of these buildings responds to what Sigfried Giedion, (1971- 1975. p.3) defines as the final stage of the first conception of space, which culminates with Greek architecture where buildings stand as volumes of radial spaces, interacting through presence, where the colonnade of the Greek temple, generator of shadow, plays a determining role. The colonnade in the buildings of the Institute of Pathological Anatomy and Tropical Medicine can only be considered as part of this precise architectural and urban intention, which must be interpreted as an effort to recompose a totality conditioned by the disproportionate presence of the Clinical Hospital building, which Villanueva was unable to balance completely through the relationships with the institutes and, for this reason, he applies the disintegration of the presence of the Clinical Hospital assigned to Mateo Manaure (1954) through the use of color.

It should be pointed out, without suggesting that this is a literal and direct reference, that for Giedion this first conception of space already expresses a new way of life, the democratic way of life; a sense that coincides with the appreciation of the architecture of the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas by Sibyl Moholy-Nagy (1964, p.35) as “…a means that will stimulate the student to improve himself, without rejecting the democratic spirit… to create an image of university life whose realization could only be fulfilled in the future“. In the case of the School of Medicine, this future is clearly associated with its conception as a faculty based on research institutes, responsible for theoretical-practical training, which is nourished by the development of scientific research; while practical-theoretical training takes place mainly at the Clinical Hospital.

It is not clear, from the above architectural considerations regarding the medical buildings, whether it is perceived that the essential content has been designed, far beyond professional training, to be one of the fundamental pieces in the construction of a full scientific development of the country, a basic condition of all modernity that, after 80 years, we are still far from achieving.

References:

- Saber ver la arquitectura. Bruno Zevi, Poseidon Editor, Buenos Aires, Argentina. (1948-1976. p 28)

- El concepto del espacio arquitectónico. Giulio Carlo Argán. Nueva Visión Editor, Buenos Aires, Argentina. (1973. p17)

- La arquitectura, fenómeno de transición. Sigfried Giedion, Gustavo Gili Editor, Barcelona, Spain. (1975. p 3)

- Carlos Raúl Villanueva y la arquitectura de Venezuela, Sibyl Moholy-Nagy. Lectura Editor, Caracas, Venezuela. (1964. p.35)

- Architect Alfredo Mariño Elizondo. Caracas, March 6, 2023.

The Institute’s access rampLuis Razetti Basic School of Medicine

The Institute’s access rampLuis Razetti Basic School of Medicine This is a view of the concrete fretwork over the main access to the second floor of the Basic School, which guarantees natural ventilation and illumination. The restoration works restored its original colors.Tropical Medicine Institute

This is a view of the concrete fretwork over the main access to the second floor of the Basic School, which guarantees natural ventilation and illumination. The restoration works restored its original colors.Tropical Medicine Institute Those are views of the works already carried out in the headquarters building of this institute. In the first, the double-height portico with cylindrical columns in which the architect placed the stairway from the main entrance to the corridor leading to the classrooms and teaching laboratories already recovered, as shown in the second picture.

Those are views of the works already carried out in the headquarters building of this institute. In the first, the double-height portico with cylindrical columns in which the architect placed the stairway from the main entrance to the corridor leading to the classrooms and teaching laboratories already recovered, as shown in the second picture.

The headquarters building of the Dr. Felix Pifano C Tropical Medicine Institute

The headquarters building of the Dr. Felix Pifano C Tropical Medicine Institute Those are two teaching laboratories after being refurbished and equipped.

Those are two teaching laboratories after being refurbished and equipped.

The Serpentarium after its total recovery: friezes, floors, metallic ironwork, painting in its original colors, and waterproofing.

The Serpentarium after its total recovery: friezes, floors, metallic ironwork, painting in its original colors, and waterproofing.  This is the mural by Mateo Manaure during its restoration. This artwork, made of metallic reliefs with machinist references, is located on the facade of the Industrial Technical School building (now the School of Sciences).

This is the mural by Mateo Manaure during its restoration. This artwork, made of metallic reliefs with machinist references, is located on the facade of the Industrial Technical School building (now the School of Sciences). Chronology of works at the Ciudad Universitaria de CaracasIndustrial Technical School

Chronology of works at the Ciudad Universitaria de CaracasIndustrial Technical School

\Architect Villanueva started the project of the Industrial Technical School ETI for CUC between 1946 and 1947. ETI is intended for pre-university technical training. It is located to the southwest of the university complex. In this project, the architect began to use brise soileis for solar protection and integrated a mural on the south facade of the laboratories. The mural is a work of Venezuelan artist Mateo Manaure. The building was completed in 1950.Student and Faculty HousingThe student housing was designed between 1948 and 1951 and construction began the following year and was completed in 1952.

\Architect Villanueva started the project of the Industrial Technical School ETI for CUC between 1946 and 1947. ETI is intended for pre-university technical training. It is located to the southwest of the university complex. In this project, the architect began to use brise soileis for solar protection and integrated a mural on the south facade of the laboratories. The mural is a work of Venezuelan artist Mateo Manaure. The building was completed in 1950.Student and Faculty HousingThe student housing was designed between 1948 and 1951 and construction began the following year and was completed in 1952.

Botanical Institute

Botanical Institute The Botanical Institute building is composed of three parallelepipeds set perpendicularly and connected by patios, ramps, and hallways. There is also the trapezoidal-shaped auditorium, with a capacity for three hundred people.There is a mural by Wifredo Lam near the auditorium entrance, as well as a wooden mural by Francisco Narváez. It was designed between 1949-1952. Its construction was completed in 1955.Botanical GardenIt was designed between 1948 and 1952 and its construction was completed in 1957. However, since 1945 the scientific work of reforestation and planting of exotic trees had already begun under the direction of Dr. Tobias Lasser. It has an area of 68 hectares where there are two lagoons, one at each end. This plant museum and research field is a living plant showcase with more than 2.500 species.

The Botanical Institute building is composed of three parallelepipeds set perpendicularly and connected by patios, ramps, and hallways. There is also the trapezoidal-shaped auditorium, with a capacity for three hundred people.There is a mural by Wifredo Lam near the auditorium entrance, as well as a wooden mural by Francisco Narváez. It was designed between 1949-1952. Its construction was completed in 1955.Botanical GardenIt was designed between 1948 and 1952 and its construction was completed in 1957. However, since 1945 the scientific work of reforestation and planting of exotic trees had already begun under the direction of Dr. Tobias Lasser. It has an area of 68 hectares where there are two lagoons, one at each end. This plant museum and research field is a living plant showcase with more than 2.500 species.

The area is inhabited by multiple species of birds and insects. It has a flat area and another that was developed on the mountainside. In the first one thematic garden were created, such as the arboretum, the palmetum (with the largest number of varieties in Latin America), the xerophilic garden, a bromeliarium, a tropical forest area, an area of araceae and zingiberaceae and a medical garden. It was opened to the public in 1958.

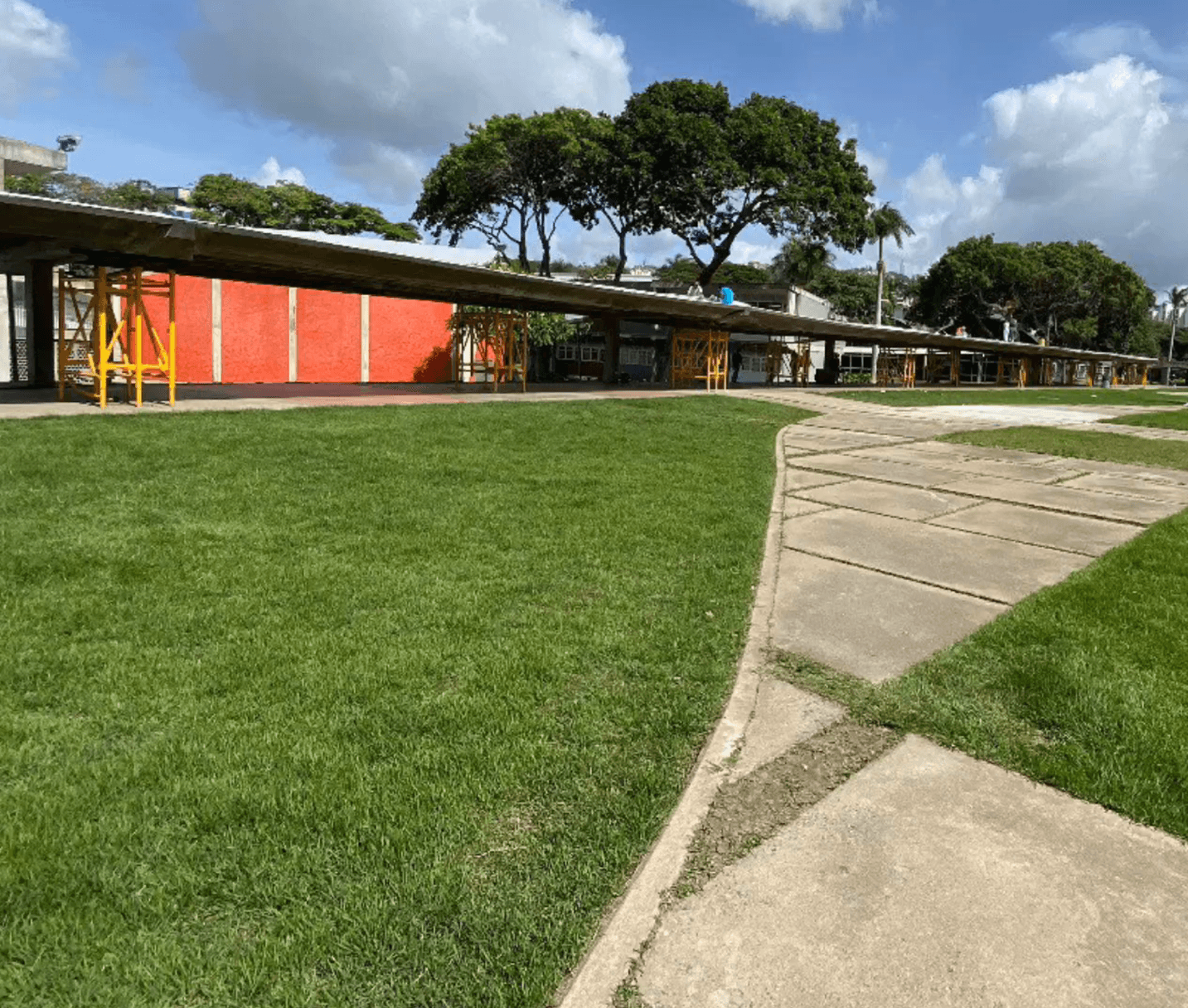

The area is inhabited by multiple species of birds and insects. It has a flat area and another that was developed on the mountainside. In the first one thematic garden were created, such as the arboretum, the palmetum (with the largest number of varieties in Latin America), the xerophilic garden, a bromeliarium, a tropical forest area, an area of araceae and zingiberaceae and a medical garden. It was opened to the public in 1958.Covered walkways

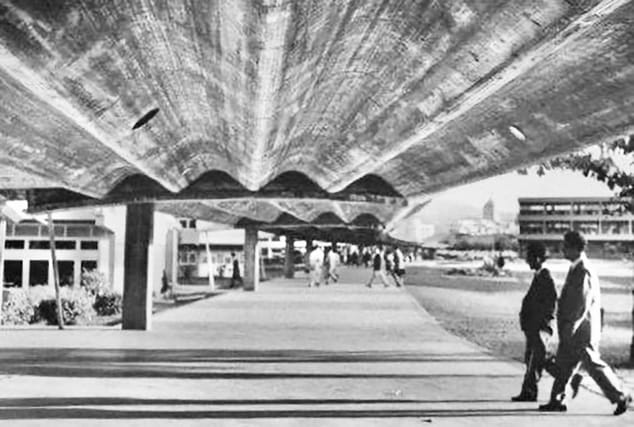

Carlos Raúl Villanueva connected the entire complex of buildings of the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas with 2 km of covered walkways, built in reinforced concrete and pre-compressed concrete using the “Morandi System”. With the use of this type of concrete, it was possible to achieve slenderness in the roofs built, despite the 15 m distance between the supports.

On June 17, 2020, a tensor of a section of Walkway Number 5, in front of the School of Humanities and Education, failed due to corrosion and collapsed, fortunately without injury or casualties. One year later, in July 2021, the National Government created the Presidential Commission for the Recovery of the UCV, which focused as a first step to carry out diagnostic inspections of these structures, and then dismantle the collapsed section.

Consequently, once the structural study of all the existing Covered Walkways at the CUC was completed, some sections were shored up as a safety measure.

An international competition for the reconstruction of this walkway is currently being evaluated, in collaboration with UNESCO.

The Covered Walkways

The covered walkways, one of the outstanding features of the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas, were designed by Carlos Raúl Villanueva in association with the company Precomprimido, C.A., integrated by engineers Juan Otaola and Oscar Benedetti. These were designed and built progressively in accordance with the progress of the construction of the complex buildings.

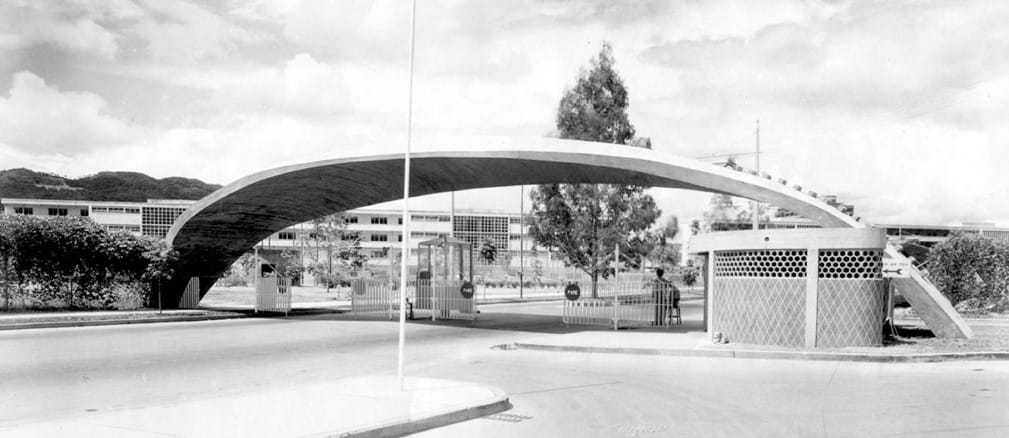

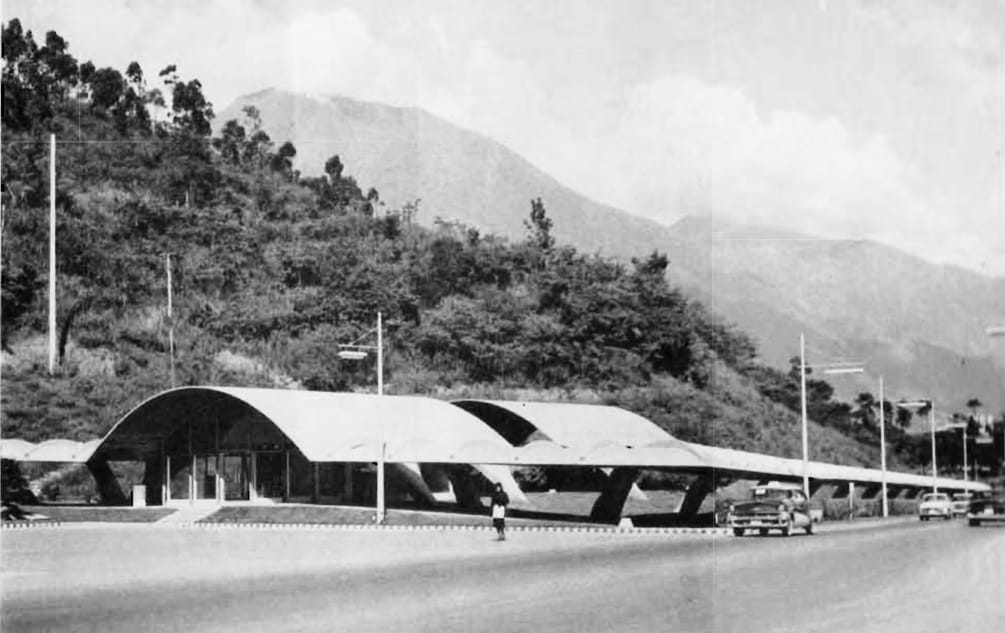

Between 1949 and 1953 were built: the walkway that connects the Dining Hall with the Store was built; in 1951 the walkway of the Faculty of Engineering; in 1952 the walkway that connects the Rectorate with the Museum; in 1953 the Access Shells to the CUC, the one that connects Experimental Medicine with the Rectorate Square, the one that covers from the access of Plaza Venezuela to the Institute of Tropical Medicine; in 1954 the walkway of the School of Humanities and finally in 1956 those of the School of Architecture.

Access Shells

This structure was designed for the two main entrances: Plaza Venezuela and Los Chaguaramos urbanization.

Pump Sheds And Power Transformers

This beautiful independent structure was designed to contain technical equipment in constant operation. This building is the juncture point between the covered walkway entering the university from the north, Plaza Venezuela, and the Medical School Complex buildings.

The university clock mechanism was recovered and painted with the original colors and is now visible and audible from many places on campus.Rectorate Plaza

The university clock mechanism was recovered and painted with the original colors and is now visible and audible from many places on campus.Rectorate Plaza

In accordance with the project developed by Villanueva, the Plaza Cubierta received a complete landscaping restoration.The Cultural Center was designed by Carlos Raúl Villanueva in 1952. It is composed of the Rectorate Plaza, the Museum, the Rectorate Building, the Communications Building and the Clock Tower, the Plaza Cubierta, the Aula Magna and the Air Conditioning Cooling Tower, the Conference Hall, the Concert Hall, the Central Library.

In accordance with the project developed by Villanueva, the Plaza Cubierta received a complete landscaping restoration.The Cultural Center was designed by Carlos Raúl Villanueva in 1952. It is composed of the Rectorate Plaza, the Museum, the Rectorate Building, the Communications Building and the Clock Tower, the Plaza Cubierta, the Aula Magna and the Air Conditioning Cooling Tower, the Conference Hall, the Concert Hall, the Central Library. Museum

Museum Rectorate Building

Rectorate Building  Communications Building

Communications Building Clock Tower

Clock Tower

Two views of the Aula Magna during its fumigation.

Two views of the Aula Magna during its fumigation. ´´

´´ The entire roof of the Administrative-Cultural Complex was waterproofed. The entire Cultural Administrative Complex was built between 1952 and 1953. It was officially inaugurated in March 1954 with the Tenth Inter-American Conference of Heads of State and Government held in Caracas.

The entire roof of the Administrative-Cultural Complex was waterproofed. The entire Cultural Administrative Complex was built between 1952 and 1953. It was officially inaugurated in March 1954 with the Tenth Inter-American Conference of Heads of State and Government held in Caracas. The Synthesis of the Arts It was Maestro Villanueva, the curator of the artistic heritage of the C.U.C., who selected the artists and artworks to be incorporated into the complex, all representative of the plastic production of the time. He wanted to create a close connection between each artwork and the public environment, using their strength and integrating them with the architecture and the spaces he created. The location of each artwork was the product of arduous reflections and rehearsals. He personally contacted each of the artists and rejected some of them. He told them what he wanted, and described the location their artwork would occupy and next to which other artwork it would be placed. The intention was to design a succession of points of view along the different possible routes in the Plaza. The artwork, its dimension, scale, color, creation technique, response to the light, its presence in the space, delimited by the roof of the square, open under the blue sky or under the magnificent and imposing structure of the Aula Magna, enriches the perception in such a way that each time the visitor takes a different route is very distinct from the previous one. Each time the senses are strongly stimulated.

The Synthesis of the Arts It was Maestro Villanueva, the curator of the artistic heritage of the C.U.C., who selected the artists and artworks to be incorporated into the complex, all representative of the plastic production of the time. He wanted to create a close connection between each artwork and the public environment, using their strength and integrating them with the architecture and the spaces he created. The location of each artwork was the product of arduous reflections and rehearsals. He personally contacted each of the artists and rejected some of them. He told them what he wanted, and described the location their artwork would occupy and next to which other artwork it would be placed. The intention was to design a succession of points of view along the different possible routes in the Plaza. The artwork, its dimension, scale, color, creation technique, response to the light, its presence in the space, delimited by the roof of the square, open under the blue sky or under the magnificent and imposing structure of the Aula Magna, enriches the perception in such a way that each time the visitor takes a different route is very distinct from the previous one. Each time the senses are strongly stimulated. Plaza Cubierta

Plaza Cubierta The Conference Hall

The Conference Hall The Concert Hall

The Concert Hall Aula Magna

Aula Magna Aula Magna is considered the most beautiful artwork built in the country.Central Library

Aula Magna is considered the most beautiful artwork built in the country.Central Library “The Plaza Cubierta of the Ciudad Universitaria is an expression and an evident result of the revisionist process. Its own structure shows it: a plaza that is not a single, coherent place of panoramic vision, but a succession of points of view that are connected and articulated around different focal points, of high or low profile, discovering the space and the surprising factors in a strictly calculated cinematographic sequence. There is a record in the archives of how Villanueva dedicated an extraordinary amount of time to refine this space until all its strings vibrate. And then the roof: the plaza is covered; it rescues and defines what could be its place in the world. The sun and rain of the tropics do not recall the Mediterranean squares, Florentine or Sienese squares, much less Parisian squares. The tropics, as climate, temperature, breeze, and calculation of sunlight, is another instrument of conscience and responsibility, but above all of sensibility, which Villanueva internalizes with time, and with which he submits to criticism and revision all that he has learned from modern European architecture. Light and its radiance, the indeterminate color of the light that humidity purifies or distempers according to the hours in a vapor of heat, are confirmed as working tools. The courtyards, the grooves, the sun’s rays, but also the penumbra and the saving shadow, as Tanizaki would say, are admirable constructive material. The roof, gray, flat, and smooth, with its elementary structure, fulfills its purpose, nothing more and nothing less. It does not ask for attention because it would take it away from the sequence of the route. It is an anonymous ceiling, but it is the expression of a point of view, of an environmental perspective, of a very clear awareness of planetary location: in the tropics, the most important thing is to build ceilings. An artist, ambiguous for other reasons, for a long time on the edge between the West and the East, the Sinhalese Geoffrey Bawa, said precisely that in the tropics the ceiling is everything.Next to it, the Aula Magna is a monumental piece. Structure and visual and acoustic functionality dominate the original composition. Here is the genius of Villanueva, who summons a happy madman like Sandy Calder to collect and expand his old-school humanist interest in the unification of the arts, using the verb of Le Corbusier and Van Doesburg, to create this poem dedicated to the enveloping form, to modern joy, to the tremendous leap of scale that was implicit in the avant-garde manifestos of the thirties. What in Europe had been a request and a utopia, a dream and a desire, words and projects, becomes reality twenty years later in this small land of grace of Venezuela. With the force of a unique episode, the Aula Magna is the highest and most magnificent artwork in the entire history of the country and surely one of the most interesting and significant in Latin America and the world. The synthesis of the arts, the project that Villanueva defended so much and within whose content he created impressive works, was a short episode without continuity. What remained was the experience of a past whose future had no space to reproduce and grow. The task that remains is to reflect on the virtues provided by fate that grants miracles and also meditate on the mysterious rules that govern fortunate and tragic but unrepeatable events. At the same time, it is necessary to ponder on the public awareness of the duty to turn a vibrant work such as the Aula Magna and its surrounding complex into an emblem of common socialization and solidarity, both born as perfect bearers of a public mission.La Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas en la obra de Carlos Raúl Villanueva. Juan Pedro Posani. International Seminar on Modern Heritage, Universidad Pontificia Católica de Chile, Santiago de Chile. 2003mage-10530-1-1.tiff” />

“The Plaza Cubierta of the Ciudad Universitaria is an expression and an evident result of the revisionist process. Its own structure shows it: a plaza that is not a single, coherent place of panoramic vision, but a succession of points of view that are connected and articulated around different focal points, of high or low profile, discovering the space and the surprising factors in a strictly calculated cinematographic sequence. There is a record in the archives of how Villanueva dedicated an extraordinary amount of time to refine this space until all its strings vibrate. And then the roof: the plaza is covered; it rescues and defines what could be its place in the world. The sun and rain of the tropics do not recall the Mediterranean squares, Florentine or Sienese squares, much less Parisian squares. The tropics, as climate, temperature, breeze, and calculation of sunlight, is another instrument of conscience and responsibility, but above all of sensibility, which Villanueva internalizes with time, and with which he submits to criticism and revision all that he has learned from modern European architecture. Light and its radiance, the indeterminate color of the light that humidity purifies or distempers according to the hours in a vapor of heat, are confirmed as working tools. The courtyards, the grooves, the sun’s rays, but also the penumbra and the saving shadow, as Tanizaki would say, are admirable constructive material. The roof, gray, flat, and smooth, with its elementary structure, fulfills its purpose, nothing more and nothing less. It does not ask for attention because it would take it away from the sequence of the route. It is an anonymous ceiling, but it is the expression of a point of view, of an environmental perspective, of a very clear awareness of planetary location: in the tropics, the most important thing is to build ceilings. An artist, ambiguous for other reasons, for a long time on the edge between the West and the East, the Sinhalese Geoffrey Bawa, said precisely that in the tropics the ceiling is everything.Next to it, the Aula Magna is a monumental piece. Structure and visual and acoustic functionality dominate the original composition. Here is the genius of Villanueva, who summons a happy madman like Sandy Calder to collect and expand his old-school humanist interest in the unification of the arts, using the verb of Le Corbusier and Van Doesburg, to create this poem dedicated to the enveloping form, to modern joy, to the tremendous leap of scale that was implicit in the avant-garde manifestos of the thirties. What in Europe had been a request and a utopia, a dream and a desire, words and projects, becomes reality twenty years later in this small land of grace of Venezuela. With the force of a unique episode, the Aula Magna is the highest and most magnificent artwork in the entire history of the country and surely one of the most interesting and significant in Latin America and the world. The synthesis of the arts, the project that Villanueva defended so much and within whose content he created impressive works, was a short episode without continuity. What remained was the experience of a past whose future had no space to reproduce and grow. The task that remains is to reflect on the virtues provided by fate that grants miracles and also meditate on the mysterious rules that govern fortunate and tragic but unrepeatable events. At the same time, it is necessary to ponder on the public awareness of the duty to turn a vibrant work such as the Aula Magna and its surrounding complex into an emblem of common socialization and solidarity, both born as perfect bearers of a public mission.La Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas en la obra de Carlos Raúl Villanueva. Juan Pedro Posani. International Seminar on Modern Heritage, Universidad Pontificia Católica de Chile, Santiago de Chile. 2003mage-10530-1-1.tiff” />  The university clock mechanism was recovered and painted with the original colors and is now visible and audible from many places on campus.Rectorate Plaza

The university clock mechanism was recovered and painted with the original colors and is now visible and audible from many places on campus.Rectorate Plaza

In accordance with the project developed by Villanueva, the Plaza Cubierta received a complete landscaping restoration.The Cultural Center was designed by Carlos Raúl Villanueva in 1952. It is composed of the Rectorate Plaza, the Museum, the Rectorate Building, the Communications Building and the Clock Tower, the Plaza Cubierta, the Aula Magna and the Air Conditioning Cooling Tower, the Conference Hall, the Concert Hall, the Central Library.

In accordance with the project developed by Villanueva, the Plaza Cubierta received a complete landscaping restoration.The Cultural Center was designed by Carlos Raúl Villanueva in 1952. It is composed of the Rectorate Plaza, the Museum, the Rectorate Building, the Communications Building and the Clock Tower, the Plaza Cubierta, the Aula Magna and the Air Conditioning Cooling Tower, the Conference Hall, the Concert Hall, the Central Library. Museum

Museum Rectorate Building

Rectorate Building  Communications Building

Communications Building Clock Tower

Clock Tower

Swimming Pool – Gymnasiums

1. Access ramps to the swimming pool grandstands.

2. Entrance to the different facilities located on the first floor during their recovery.

3. Reconstruction of the two pools and the adjacent beach.

In the background, there is the chimney of the old Casona de la Hacienda Ibarra.

4. The Olympic Pool and the covered grandstand during restoration works.

4. The Olympic Pool and the covered grandstand during restoration works.

5. The restoration works included: the recovery of the pool, the illumination, and a color test for the interior lining of the pool.

6. In the Pump room maintenance was performed on the technical equipment.

7. Gymnastics Room

7. Gymnastics Room

8. Fencing Room

9. Judo Hall

10. Table Tennis Room

11. In the Tennis Courts, which are located next to the Pool-Gym complex and in front of the University Housing, the restoration works restored fences and illumination.

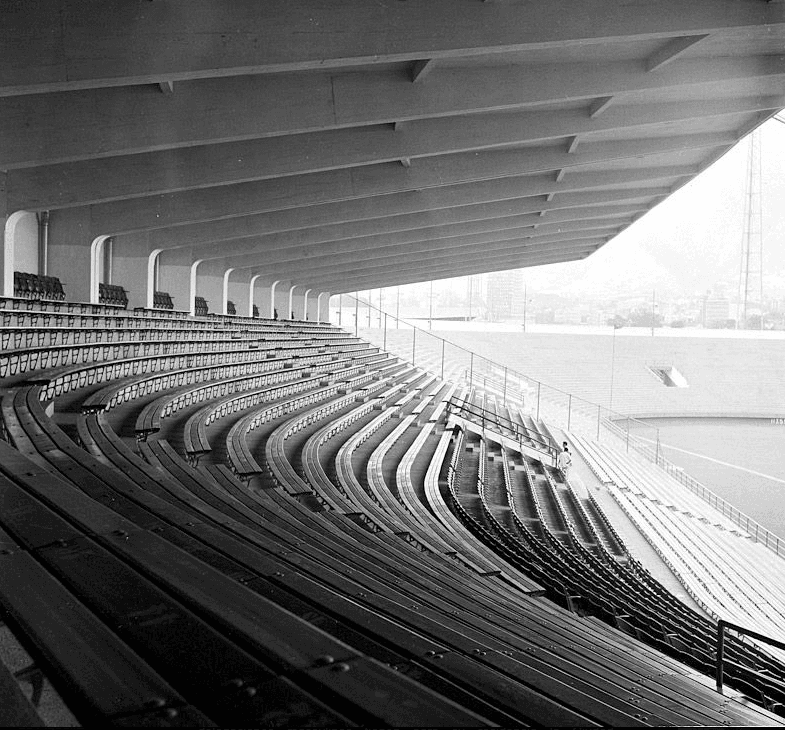

12. Olympic Stadium

It was designed between 1949-1951 and finished in 1952 to host the Bolivarian Games. The Stadium has a capacity of 50.000 spectators.

13. CUC-UCV Olympic Stadium. View of the covered grandstand.

Villanueva’s treatment of space, “the limit, which is neither interior nor exterior,” is once again evident in his design of the grandstand.

14. Baseball Stadium and the Olympic Stadium in the background.

15. Court of Honor and Olympic Stadium in the background.

Pool and Gymnasium Complex Building

1. The reconstruction of the CVP cafeteria in accordance with Villanueva’s project

1. The reconstruction of the CVP cafeteria in accordance with Villanueva’s project 2. Swimming pool and gymnasium Complex. CVP Cafeteria under reconstruction.

2. Swimming pool and gymnasium Complex. CVP Cafeteria under reconstruction. 3. The CVP Cafeteria, located between the Pool and Gymnasium Complex and the Student Housing, during the restoration work.

3. The CVP Cafeteria, located between the Pool and Gymnasium Complex and the Student Housing, during the restoration work. 4. In the University Housing Building were completed different masonry works, metalwork, sanitary installations, electrical installations, and painting, all in accordance with the original project.

4. In the University Housing Building were completed different masonry works, metalwork, sanitary installations, electrical installations, and painting, all in accordance with the original project. 6. This is a view of one of the University Housing Buildings from the swimming pool.The proximity of the sports facilities ratifies Villanueva’s thought of students’ need to develop body and mind in a complementary manner.

6. This is a view of one of the University Housing Buildings from the swimming pool.The proximity of the sports facilities ratifies Villanueva’s thought of students’ need to develop body and mind in a complementary manner. 7. UCV University Dining Hall. Photo by Julio César Mesa.

7. UCV University Dining Hall. Photo by Julio César Mesa. 8. Internal view of the University Dining Hall.

8. Internal view of the University Dining Hall. 10. University Shop and Dining Hall. Ceramic tiling of the store was designed by Francisco Narváez.

10. University Shop and Dining Hall. Ceramic tiling of the store was designed by Francisco Narváez. Mechanical and Electrical LaboratoryThis building of the School of Engineering received the aforementioned repairs, as well as the reconstruction of its windows and the application of paint in the original colors.

Mechanical and Electrical LaboratoryThis building of the School of Engineering received the aforementioned repairs, as well as the reconstruction of its windows and the application of paint in the original colors. School of Chemistry, Petroleum and Geology

School of Chemistry, Petroleum and Geology  School of Chemistry, Petroleum and Geology

School of Chemistry, Petroleum and Geology Physics Laboratory

Physics Laboratory School of Engineering. Basic SchoolParticular attention was given to the thorough maintenance of the covered walkways that connect the buildings of the Engineering Faculty Complex.

School of Engineering. Basic SchoolParticular attention was given to the thorough maintenance of the covered walkways that connect the buildings of the Engineering Faculty Complex. Faculty of Engineering. Basic School – Amphitheatrical Classrooms The furniture in this amphitheater classroom was repaired, the blackboards replaced, the lighting improved and the escape routes restored in accordance with standards.

Faculty of Engineering. Basic School – Amphitheatrical Classrooms The furniture in this amphitheater classroom was repaired, the blackboards replaced, the lighting improved and the escape routes restored in accordance with standards. Faculty of Engineering. Basic School. First floor study area These study areas were adapted to their use, recovering the original height of the space, eliminating the ceiling, and installing more responsive lighting and resistant furniture.

Faculty of Engineering. Basic School. First floor study area These study areas were adapted to their use, recovering the original height of the space, eliminating the ceiling, and installing more responsive lighting and resistant furniture. Faculty of Engineering. Basic School, first floor study areas.

Faculty of Engineering. Basic School, first floor study areas. School of Engineering. Basic School internal staircaseIn this building were recovered several partition walls which had been covered. These walls were originally built with perforated concrete blocks that allowed adequate ventilation and lighting in these public circulation spaces. School of Engineering Building Complex The buildings for the School of Engineering were designed between 1949 and 1950, and construction began that same year. The building for the School of Sanitary Engineering was designed between 1963 and 1967 and construction was completed in 1970.

School of Engineering. Basic School internal staircaseIn this building were recovered several partition walls which had been covered. These walls were originally built with perforated concrete blocks that allowed adequate ventilation and lighting in these public circulation spaces. School of Engineering Building Complex The buildings for the School of Engineering were designed between 1949 and 1950, and construction began that same year. The building for the School of Sanitary Engineering was designed between 1963 and 1967 and construction was completed in 1970. 1. Basic School 2. Library and Auditorium3. School of Chemistry, Petroleum andGeology4. Physics Laboratory5. Mechanics and Electrical Laboratory6. Biology Laboratory7. Materials Testing Laboratory8. Institute of Materials and Structural Models9. Hydraulics Laboratory10. Sanitary Engineering School

1. Basic School 2. Library and Auditorium3. School of Chemistry, Petroleum andGeology4. Physics Laboratory5. Mechanics and Electrical Laboratory6. Biology Laboratory7. Materials Testing Laboratory8. Institute of Materials and Structural Models9. Hydraulics Laboratory10. Sanitary Engineering School 1. Basic Engineering BuildingThis is the image of the completed building. It shows the north-facing set of classrooms on each floor before their exterior partitions were painted.2. Library and Auditorium

1. Basic Engineering BuildingThis is the image of the completed building. It shows the north-facing set of classrooms on each floor before their exterior partitions were painted.2. Library and Auditorium When comparing the Basic School project with that of the Library and Auditorium of the same faculty, it is evident the approach given by Villanueva to the expressive language of modern architecture that he adopted at the beginning of the 1950s. The construction of this building was completed in 1953 with a mural by the Venezuelan artist Alejandro Otero.

When comparing the Basic School project with that of the Library and Auditorium of the same faculty, it is evident the approach given by Villanueva to the expressive language of modern architecture that he adopted at the beginning of the 1950s. The construction of this building was completed in 1953 with a mural by the Venezuelan artist Alejandro Otero. School of Chemistry, Petroleum and GeologyDesigned between 1949-1950

School of Chemistry, Petroleum and GeologyDesigned between 1949-1950 Physics Laboratory Today this laboratory is the headquarters of the Applied Physics Department of the Engineering School of the UCV.

Physics Laboratory Today this laboratory is the headquarters of the Applied Physics Department of the Engineering School of the UCV. Mechanical and Electrical Laboratory.

Mechanical and Electrical Laboratory.  1. Sanitary Engineering Building. west facade

1. Sanitary Engineering Building. west facade 2. Sanitary Engineering Building. east facade

2. Sanitary Engineering Building. east facade

3/4 Views of the roofed central courtyard of the Sanitary Engineering building around which the spaces are articulated in this way: classrooms, laboratories, offices and services.

3/4 Views of the roofed central courtyard of the Sanitary Engineering building around which the spaces are articulated in this way: classrooms, laboratories, offices and services. 5. Central roofed courtyard of the Sanitary Engineering School building.

5. Central roofed courtyard of the Sanitary Engineering School building. 6. Biology LaboratoryDesigned between 1949-1953 and built in 1950.

6. Biology LaboratoryDesigned between 1949-1953 and built in 1950. 7. Institute of Materials and Structural ModelingThe building project for this 1.220 m2 testing laboratory was completed in 1963. The roof was built with prefabricated and prestressed elements, which have a length of 22.50 meters and a width of 2.5 meters each.

7. Institute of Materials and Structural ModelingThe building project for this 1.220 m2 testing laboratory was completed in 1963. The roof was built with prefabricated and prestressed elements, which have a length of 22.50 meters and a width of 2.5 meters each. 8. Hydraulics LaboratoryThis laboratory was designed by architect Villanueva in 1952 and its construction was completed in 1960.

8. Hydraulics LaboratoryThis laboratory was designed by architect Villanueva in 1952 and its construction was completed in 1960. 9. This is the east facade of the Hydraulic Engineering Laboratory after its original colors have been recovered and its windows have been fixed.

9. This is the east facade of the Hydraulic Engineering Laboratory after its original colors have been recovered and its windows have been fixed.  10. A view of the Hydraulic Engineering Laboratory during the process of restoring the original colors and deep maintenance of the concrete sun protection elements.

10. A view of the Hydraulic Engineering Laboratory during the process of restoring the original colors and deep maintenance of the concrete sun protection elements. 11. School of Engineering. Hydraulic Engineering Laboratory

11. School of Engineering. Hydraulic Engineering Laboratory  12. School of Humanities and EducationIt was designed between 1953-1956. The 19.000 m2 building was built between 1954 and 1959.

12. School of Humanities and EducationIt was designed between 1953-1956. The 19.000 m2 building was built between 1954 and 1959. 13. The School of Humanities and Education Auditorium with an intervention by the artist Víctor Valera.

13. The School of Humanities and Education Auditorium with an intervention by the artist Víctor Valera. 14. School of Dental MedicineThis tower, which complements the Medical Complex, was designed between 1955 and 1957. It was built in 1957. The polychrome of its facades was made by Omar Carreño.

14. School of Dental MedicineThis tower, which complements the Medical Complex, was designed between 1955 and 1957. It was built in 1957. The polychrome of its facades was made by Omar Carreño. 15. Pharmacy SchoolThis building, which is also part of the Medicine Complex, was designed almost simultaneously with the School of Dental Medicine and was built in 1960. The polychromy of its facades is done by the artist Alejandro Otero. he restitution and recovery of original spaces, removing constructions, and improving classrooms, study rooms, and restrooms. There was also made wood carpentry, metal carpentry, ceiling removal, placement of lighting fixtures, drainpipes, waterproofing and landscaping.

15. Pharmacy SchoolThis building, which is also part of the Medicine Complex, was designed almost simultaneously with the School of Dental Medicine and was built in 1960. The polychromy of its facades is done by the artist Alejandro Otero. he restitution and recovery of original spaces, removing constructions, and improving classrooms, study rooms, and restrooms. There was also made wood carpentry, metal carpentry, ceiling removal, placement of lighting fixtures, drainpipes, waterproofing and landscaping. Mechanical and Electrical LaboratoryThis building of the School of Engineering received the aforementioned repairs, as well as the reconstruction of its windows and the application of paint in the original colors.

Mechanical and Electrical LaboratoryThis building of the School of Engineering received the aforementioned repairs, as well as the reconstruction of its windows and the application of paint in the original colors. School of Chemistry, Petroleum and Geology

School of Chemistry, Petroleum and Geology  School of Chemistry, Petroleum and Geology

School of Chemistry, Petroleum and Geology Physics Laboratory

Physics Laboratory School of Engineering. Basic SchoolParticular attention was given to the thorough maintenance of the covered walkways that connect the buildings of the Engineering Faculty Complex.

School of Engineering. Basic SchoolParticular attention was given to the thorough maintenance of the covered walkways that connect the buildings of the Engineering Faculty Complex. Faculty of Engineering. Basic School – Amphitheatrical Classrooms The furniture in this amphitheater classroom was repaired, the blackboards replaced, the lighting improved and the escape routes restored in accordance with standards.

Faculty of Engineering. Basic School – Amphitheatrical Classrooms The furniture in this amphitheater classroom was repaired, the blackboards replaced, the lighting improved and the escape routes restored in accordance with standards. Faculty of Engineering. Basic School. First floor study area These study areas were adapted to their use, recovering the original height of the space, eliminating the ceiling, and installing more responsive lighting and resistant furniture.

Faculty of Engineering. Basic School. First floor study area These study areas were adapted to their use, recovering the original height of the space, eliminating the ceiling, and installing more responsive lighting and resistant furniture. Faculty of Engineering. Basic School, first floor study areas.

Faculty of Engineering. Basic School, first floor study areas. School of Engineering. Basic School internal staircaseIn this building were recovered several partition walls which had been covered. These walls were originally built with perforated concrete blocks that allowed adequate ventilation and lighting in these public circulation spaces. School of Engineering Building Complex The buildings for the School of Engineering were designed between 1949 and 1950, and construction began that same year. The building for the School of Sanitary Engineering was designed between 1963 and 1967 and construction was completed in 1970.

School of Engineering. Basic School internal staircaseIn this building were recovered several partition walls which had been covered. These walls were originally built with perforated concrete blocks that allowed adequate ventilation and lighting in these public circulation spaces. School of Engineering Building Complex The buildings for the School of Engineering were designed between 1949 and 1950, and construction began that same year. The building for the School of Sanitary Engineering was designed between 1963 and 1967 and construction was completed in 1970. 1. Basic School 2. Library and Auditorium3. School of Chemistry, Petroleum andGeology4. Physics Laboratory5. Mechanics and Electrical Laboratory6. Biology Laboratory7. Materials Testing Laboratory8. Institute of Materials and Structural Models9. Hydraulics Laboratory10. Sanitary Engineering School

1. Basic School 2. Library and Auditorium3. School of Chemistry, Petroleum andGeology4. Physics Laboratory5. Mechanics and Electrical Laboratory6. Biology Laboratory7. Materials Testing Laboratory8. Institute of Materials and Structural Models9. Hydraulics Laboratory10. Sanitary Engineering School 1. Basic Engineering BuildingThis is the image of the completed building. It shows the north-facing set of classrooms on each floor before their exterior partitions were painted.2. Library and Auditorium

1. Basic Engineering BuildingThis is the image of the completed building. It shows the north-facing set of classrooms on each floor before their exterior partitions were painted.2. Library and Auditorium When comparing the Basic School project with that of the Library and Auditorium of the same faculty, it is evident the approach given by Villanueva to the expressive language of modern architecture that he adopted at the beginning of the 1950s. The construction of this building was completed in 1953 with a mural by the Venezuelan artist Alejandro Otero.

When comparing the Basic School project with that of the Library and Auditorium of the same faculty, it is evident the approach given by Villanueva to the expressive language of modern architecture that he adopted at the beginning of the 1950s. The construction of this building was completed in 1953 with a mural by the Venezuelan artist Alejandro Otero. School of Chemistry, Petroleum and GeologyDesigned between 1949-1950

School of Chemistry, Petroleum and GeologyDesigned between 1949-1950 Physics Laboratory Today this laboratory is the headquarters of the Applied Physics Department of the Engineering School of the UCV.

Physics Laboratory Today this laboratory is the headquarters of the Applied Physics Department of the Engineering School of the UCV. Mechanical and Electrical Laboratory.

Mechanical and Electrical Laboratory.  1/2 The facades of the building were restored by re-establishing the metallic carpentry of the windows (fixed glass, projecting, and shutter windows), painting and cleaning the concrete. All of the building’s roofs were waterproofed.

1/2 The facades of the building were restored by re-establishing the metallic carpentry of the windows (fixed glass, projecting, and shutter windows), painting and cleaning the concrete. All of the building’s roofs were waterproofed.

3. This is the elevator building’s covering structure, in 2 x 2 vitrified ceramic mosaic tiles in accordance with Alejandro Otero’s intervention.

3. This is the elevator building’s covering structure, in 2 x 2 vitrified ceramic mosaic tiles in accordance with Alejandro Otero’s intervention. 4. The south access covered walkway bordering the old parking lot, where the landscaping was restored.

4. The south access covered walkway bordering the old parking lot, where the landscaping was restored. 6. Covered west access walkway, bordering the old parking lot, which connects the buildings of the School of Architecture and Urban Planning with the School of Engineering.

6. Covered west access walkway, bordering the old parking lot, which connects the buildings of the School of Architecture and Urban Planning with the School of Engineering. 7. The lobby of the faculty building with its views through the openwork block walls.

7. The lobby of the faculty building with its views through the openwork block walls. 8. The former textures laboratory, today called “Taller Galia”, has been completely recovered as a teaching classroom for the architectural design course.

8. The former textures laboratory, today called “Taller Galia”, has been completely recovered as a teaching classroom for the architectural design course. 9. In this amphitheater classrooms were replaced the windows, seats, wooden platform, carpets and projection booth.

9. In this amphitheater classrooms were replaced the windows, seats, wooden platform, carpets and projection booth. 10. This is a view of the hallway where are located the Faculty’s departments and three laboratories, in the background the “Taller Galia”.

10. This is a view of the hallway where are located the Faculty’s departments and three laboratories, in the background the “Taller Galia”. 11. The building’s lighting was restored, changing the different models of lamps in interior spaces and placing reflectors and luminaires in exterior areas.

11. The building’s lighting was restored, changing the different models of lamps in interior spaces and placing reflectors and luminaires in exterior areas. School of Architecture and Urban Planning12. This 18.240 m2 building, a masterpiece by Villanueva, was designed between 1954-1956 and built throughout 1956.

School of Architecture and Urban Planning12. This 18.240 m2 building, a masterpiece by Villanueva, was designed between 1954-1956 and built throughout 1956.  13. Its design, height, shape, three-dimensional treatment, and colors (blue, black, and white) were decided in collaboration with the famous Venezuelan artist Alejandro Otero, making this building of the School of Architecture and Urban Planning easily recognizable from any point of the University City as well as from other parts of the capital city.

13. Its design, height, shape, three-dimensional treatment, and colors (blue, black, and white) were decided in collaboration with the famous Venezuelan artist Alejandro Otero, making this building of the School of Architecture and Urban Planning easily recognizable from any point of the University City as well as from other parts of the capital city. 14. The first floor of the building is a public citadel with multiple activities where the space is composed of changing scales and levels: exhibition galleries, library, cafeteria, auditorium, and laboratories, all connected through hallways and small internal gardens delimited by openwork walls, which develop the modern discourse of spatial fluidity, moving from one location to another without abrupt changes. ABOUT THE BUILDING OF THE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNINGThe School of Architecture and Urban Planning building, designed by architect Carlos Raúl Villanueva, was built between 1954 and 1956 on a 5.600 m² lot. This is a central building in Villanueva’s work, which was conceived under a very personal principle that embraced the academic theories of the Bauhaus. Six areas of work were clearly differentiated -composition, construction, painting and sculpture, urbanism and theory-, and all of them revolve around the central nine-story tower, recognizable from any point in the University City, due to its shape, blue color and three-dimensional design.The nine-story tower, built on an expressive system of concrete porticoes, is a direct Corbusian reference. This prism of accentuated horizontality rationally sets its north-south orientation. To the north, its facade opens fully to the visual wings of the mountain and reveals in a gesture of solar protection an expressive brie-soleil; to the south, an openwork wall serves as a protection to the intense tropical light; to the east, the facade closes completely, sculpturally manifesting the importance of the service staircase; to the west, the facade closes definitively. In these last two facades, nine-story-high vertical walls support Alejandro Otero’s artwork, which dematerializes the weight of the architectural body through the geometric interaction of variations in blue.The first floor of the building forms a public citadel of multiple activities, defined by its changes of scale and level: exhibition halls, library, cafés, auditorium and laboratories, connected by hallways and small internal gardens and delimited by openwork walls, develop the modern discourse of spatial fluidity, passing from one space to another without abrupt changes. The standard floors are structured around a succession of north-facing classrooms connected by a wide hallway to the south: the functionality of the floor plan is organized around an expressive lateral nucleus of stairways and elevators.On the first floor, around the tower, and to the north, there are the composition laboratories where illumination and ventilation details have been studied and proportions arranged for greater comfort. In this space it is remarkable the plastic dimension acquired by the folds of its roofs, which receive water, air, and light, turning the concept of protection into a source of intense variations. To the south, and as two independent volumes that show extreme functionality, the auditorium and the double-height library emerge.The rawness of this building was conceived by Villanueva as an architectural exercise. Throughout its spaces, it is easy to discern the structural technologies, the infrastructure’s behavior, and the attention to detail as a manifesto of architectural composition.Henrique VeraReferencesCarlos Raúl Villanueva: un moderno en Sudamérica. Juan Pedro Posani, William Niño, Luis E. Pérez Oramas. National Art Gallery Foundation, Caracas. 1999.Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas. Patrimonio Mundial. Itinerant Exhibition 2002-2003. Abner Colmenares et al. UNESCO, Universidad Central de Venezuela, FAU UCV. 2002.

14. The first floor of the building is a public citadel with multiple activities where the space is composed of changing scales and levels: exhibition galleries, library, cafeteria, auditorium, and laboratories, all connected through hallways and small internal gardens delimited by openwork walls, which develop the modern discourse of spatial fluidity, moving from one location to another without abrupt changes. ABOUT THE BUILDING OF THE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE AND URBAN PLANNINGThe School of Architecture and Urban Planning building, designed by architect Carlos Raúl Villanueva, was built between 1954 and 1956 on a 5.600 m² lot. This is a central building in Villanueva’s work, which was conceived under a very personal principle that embraced the academic theories of the Bauhaus. Six areas of work were clearly differentiated -composition, construction, painting and sculpture, urbanism and theory-, and all of them revolve around the central nine-story tower, recognizable from any point in the University City, due to its shape, blue color and three-dimensional design.The nine-story tower, built on an expressive system of concrete porticoes, is a direct Corbusian reference. This prism of accentuated horizontality rationally sets its north-south orientation. To the north, its facade opens fully to the visual wings of the mountain and reveals in a gesture of solar protection an expressive brie-soleil; to the south, an openwork wall serves as a protection to the intense tropical light; to the east, the facade closes completely, sculpturally manifesting the importance of the service staircase; to the west, the facade closes definitively. In these last two facades, nine-story-high vertical walls support Alejandro Otero’s artwork, which dematerializes the weight of the architectural body through the geometric interaction of variations in blue.The first floor of the building forms a public citadel of multiple activities, defined by its changes of scale and level: exhibition halls, library, cafés, auditorium and laboratories, connected by hallways and small internal gardens and delimited by openwork walls, develop the modern discourse of spatial fluidity, passing from one space to another without abrupt changes. The standard floors are structured around a succession of north-facing classrooms connected by a wide hallway to the south: the functionality of the floor plan is organized around an expressive lateral nucleus of stairways and elevators.On the first floor, around the tower, and to the north, there are the composition laboratories where illumination and ventilation details have been studied and proportions arranged for greater comfort. In this space it is remarkable the plastic dimension acquired by the folds of its roofs, which receive water, air, and light, turning the concept of protection into a source of intense variations. To the south, and as two independent volumes that show extreme functionality, the auditorium and the double-height library emerge.The rawness of this building was conceived by Villanueva as an architectural exercise. Throughout its spaces, it is easy to discern the structural technologies, the infrastructure’s behavior, and the attention to detail as a manifesto of architectural composition.Henrique VeraReferencesCarlos Raúl Villanueva: un moderno en Sudamérica. Juan Pedro Posani, William Niño, Luis E. Pérez Oramas. National Art Gallery Foundation, Caracas. 1999.Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas. Patrimonio Mundial. Itinerant Exhibition 2002-2003. Abner Colmenares et al. UNESCO, Universidad Central de Venezuela, FAU UCV. 2002. In this hallway were restored friezes, floors, railings and lighting.

In this hallway were restored friezes, floors, railings and lighting. A view of a hallway of the School of Humanities and Education, with a mural by Víctor Valera and an interior garden with students enjoying their resting time.

A view of a hallway of the School of Humanities and Education, with a mural by Víctor Valera and an interior garden with students enjoying their resting time. The ramp, located in the School of Humanities and Education, was restored to its original appearance with a beautiful double-height mural by Victor Valera.School of Law and Political Science

The ramp, located in the School of Humanities and Education, was restored to its original appearance with a beautiful double-height mural by Victor Valera.School of Law and Political Science A view of the School of Law and Political Sciences first-floor classrooms which face a garden near a covered hallway and the School of Economics.

A view of the School of Law and Political Sciences first-floor classrooms which face a garden near a covered hallway and the School of Economics. A classroom with glass doors that allow a panoramic view and that can be opened to extend the internal space.

A classroom with glass doors that allow a panoramic view and that can be opened to extend the internal space. View of one of the folding doors of the first-floor classroom open to the garden, equipped with laminated safety glass.

View of one of the folding doors of the first-floor classroom open to the garden, equipped with laminated safety glass. A view of the School of Law and Political Sciences with a mural by Victor Valera and an internal hallway with classrooms. In this area the friezes and floors were repaired, the metallic ironwork was repainted and the lighting was replaced, all according to the original plans of Villanueva’s project.

A view of the School of Law and Political Sciences with a mural by Victor Valera and an internal hallway with classrooms. In this area the friezes and floors were repaired, the metallic ironwork was repainted and the lighting was replaced, all according to the original plans of Villanueva’s project.  The School of Law and Political Sciences. Mural by Víctor Valera. photo LIFE

The School of Law and Political Sciences. Mural by Víctor Valera. photo LIFE The School of Humanities and Education and the School of Law and Political Sciences. Overall plan

The School of Humanities and Education and the School of Law and Political Sciences. Overall plan 10. The headquarters of the School of Sanitary Engineering was designed by Carlos Raúl Villanueva in collaboration with Gorka Dorronsoro.

10. The headquarters of the School of Sanitary Engineering was designed by Carlos Raúl Villanueva in collaboration with Gorka Dorronsoro. y11. Villanueva designed the School of Economics building between 1959 and 1964 in collaboration with Gorka Dorronsoro and Juan Pedro Posani.

y11. Villanueva designed the School of Economics building between 1959 and 1964 in collaboration with Gorka Dorronsoro and Juan Pedro Posani. 12. The ambitious structure of the Covered Gymnasium, designed by Villanueva, which was supposed to have on its top a reinforced concrete paraboloid of double curvature, calculated by the Swiss engineer Rodolfo Kaltenstadler, was never completed for the celebration of the Central American and Caribbean Games of 1957 in Caracas. As a result, the gymnasium was covered with a provisional metal roof that still exists today.